|

Stalin and the Soviet Economy |

Collectivisation |

|

Stalin aimed to modernise the Soviet economy by collectivisation and industrialisation. Agricultural collectivisation in the First Five Year Plan (1928 - 32) involved setting up collective farms (kolkhozy) and state farms (sovkhozy); in the former peasants would manage the farms as co-operatives, in the latter the State would manage the farm. In practice there were few differences between them. Theoretically, large farms would be more efficient, fewer rural workers would be needed and thus more workers would be available for industry. Coercion was used to implement this policy.

|

|

|

The collectivisation is defined as the 'second Revolution' or 'revolution from above' by Soviet historians. Bukharin and the Right interpreted the October 1917 revolution as a victory for the Bolshevik-led proletariat - revolution from below - and argued that the economy should be allowed to develop without State interference. He believed the Marxist political system would determine the economy. But Stalin wanted a faster development. His motives are not clear. The process did help to consolidate his power. He probably also believed that it was the only way to make Russia safe. He wrote “we are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in ten years. Either we do it, or we shall be crushed.”

|

|

|

In order to justify coercing the peasants Stalin's propaganda blamed the lack of modernisation of the USSR on the wealthy peasants - the Kulaks - he maintained they had to be broken as a class. Modern scholars do not believe such a class ever existed and if there were richer peasants they did not constitute exploitative land-owners. The Kulak myth was used to justify coercing all peasants. In theory surplus grain would be exported to provide investment capital for industry and surplus peasants would be turned into industrial proletariat. In practice there never was a surplus of grain. Stalin said the lack of food was due to poor distribution and once again blamed the Kulaks as grain-monopolists. This lead to poorer peasants victimising richer peasants in some regions. Anti-Kulak squads were authorised by Stalin to persecute, arrest and deport peasants. They were supervised by the OGPU, which replaced the Cheka and would itself be renamed the NKVD in 1931.

|

|

|

From December 1929 to March 1930 nearly 60% of peasant farms were collectivised. The result was a near civil war. Stalin temporarily halted the programme, and blamed the excess on local officials. He then resumed the programme. By 1934 71.4% of peasant lands had been collectivised; by 1936 89.6% and by 1941 98.0%. The results were tragic, and agricultural output suffered terribly; the peasants were alienated. Western estimates indicate that numbers of livestock were more than halved and that average consumption of bread, potatoes, meat, lard and butter all decreased. Since towns were better supplied this means that the countryside was even more miserable. From 1932-33 there was a national famine. Vast numbers attempted to migrate to the towns and internal passports were introduced. Stalin and the government would not acknowledge that there was a famine so nothing was done about it. Isaac Deutscher calls it, 'the first purely man-made famine in history'. By 1939 productivity in agriculture in Soviet Russia had scarcely reached the level of 1913. Western historians estimate that 10-15 million Russians died of starvation during the 1930s.

|

|

Industrialisation |

|

Stalin sought to create a war economy. He believed that Western industrialisation had been brought about through production of iron and steel. His industrial drive coincided with the Great Depression, which gave ammunition to the propaganda that the West was in its final great crisis as foretold by Marx.

|

|

|

The First Five-Year Plan - October 1928 to December 1932

|

|

|

There was no real plan - merely a set of targets. Also, precise figures for the period are not available. The plan appeared to be progressing during the early stages and the targets were revised upwards twice. Output of coal, oil, iron ore and pig iron all probably doubled during this period. It was a massive propaganda project, but many Soviet people genuinely believed they were creating a better society. There was a curious blend of idealism and coercion. Young people were especially enthusiastic. There were achievements but output in steel and chemicals did not grow so impressively. There was a decline in textile manufacture and consumer goods were given low priority, and standards of living did not improve. The industrial workforce was coerced. The Shakhty trial of 1928 marked the beginning of this. In 1928 it was claimed that an anti-Soviet conspiracy was discovered amongst engineers in the town of Shakhty in the Donbass region. Engineers were put on trial. The process involved huge waste - new plant and machinery was ruined by incompetence and a rural peasantry could not be transformed overnight into an industrial workforce. Stalin blamed failures on 'saboteurs' and 'wreckers'. OGPU agents and political officers spied on managers and the workforce and denunciations were frequent and fear increased. The whole thing was a fraud - a pretence that things were successful when they weren't. There was no central planning and the actual planning was done by regional managers and workers on site.

|

|

|

The Second (January 1933 to December 1937) and the Third (January 1938 to June 1941) Five-Year Plans

|

|

|

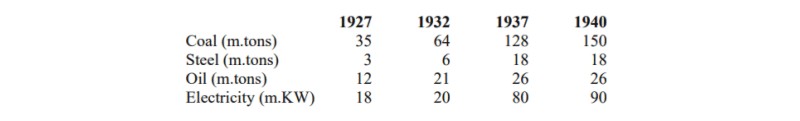

In the Second Five-Year Plan the targets were more realistic, but there was still an absence of central planning. Regions and factories often competed for scarce resources desperate to avoid being charged with failure to meet targets. There was unproductive hoarding of raw materials. All this coincided with the peak of the purges when denunciations were at their greatest. Engineers and technologists were deported by thousands to distant concentration camps. Heavy industry did progress, but consumer goods were again neglected. Propaganda was used - for example, it was said that in August 1935 Alexei Stakhanov had produced in a 5 hour shift 14 times his quota of coal. This lead to the Stakhanovite movement - encouraging workers to exceed their quotas. But conditions of soviet workers were poor. The economy was already a 'war economy' and unions were weak, and controlled by the Party. Strikes were illegal. Standards of living were lower in real terms in 1937 than in 1928. The priority was given to defence. Defence increased from 4% of industrial output in 1933 to 17% in 1937. There was a war atmosphere. The Third 5 year plan was halted by the German invasion of 1941. However, Russia was able to contend militarily with Germany by this time. E. Zaleski's estimates for output are

|

|

|

|

|

Soviet industrial output, 1927 — 1940

|

|

The Economy During Wartime, 1941 - 45 |

|

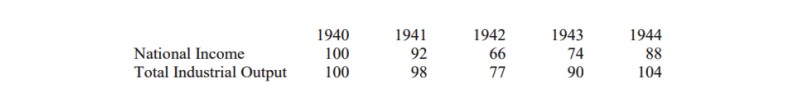

The war destroyed even the appearance of central planning. Stalin appealed for a defence of 'Mother Russia' and adopted a scorched-earth policy. By 1942 half the Soviet people were under German occupation, and 1/3rd of industry was taken. The nation had lost 60% of its iron and steel production. Whole sectors of industry were transferred to eastern USSR. Women took over work on the land. Output of coal, iron, steel, oil, electricity all collapsed dramatically by 1942. But thereafter output started to recover as the factories of the Urals came into production and lend-lease from USA became effective. Figures for National Income and total industrial output are (indexed - 1940 = 100):

|

|

|

|

|

Soviet wartime output, 1940 — 1945

|

|

|

By 1943 the Soviet Union was recovering its lost cities, with benefits to the war economy. The economy was able to produce huge volumes of arms at a time of desperate shortages. However, the famine persisted. Of the 20 million Soviet people who died during the war it is thought that 5 million died due to starvation.

|

|

Post-war Reconstruction |

|

The Soviet victory in the war increased Stalin's grip on the country. He was even more paranoid about the intentions of the West and once again prioritised defence and heavy industry. The fourth Five Year Plan (January 1946 to December 1950) aimed to restore industrial output to its pre-war levels and probably did so within 3 years, but only in heavy industry. The economy remained unbalanced. There was no integration of separate projects into a single economic strategy. By 1950 output of iron, steel, oil and electricity was double that of 1946; but agriculture continued to suffer. Living standards were still at the 1917 level. The Fifth Five Year Plan (January 1951 to December 1955) saw little change in agricultural output.

|

|

Evaluation |

|

Historians accept that the USSR's industrial revolution between 1928 and 1941 was a great achievement, but debate whether Stalin's coercion was necessary. They also debate whether the emphasis on heavy industry was appropriate, and whether it served the USSR's long-term needs. E.H. Carr acknowledges that without Stalin's war economy the USSR would have collapsed during the Second World War. But others maintain that the USSR was not in fact ready for the war and claim that the expansion of the USSR economy would have been impossible if a basis for growth did not already exist. This view is adopted by Norman Stone and Robert Conquest. Further, Alec Nove notes that during the war, 'many Russians greeted the Germans as deliverers from tyranny.' By 1953 living standards of factory workers were just higher than 1928 and those of farm workers were lower than in 1913. Khrushchev is unfairly blamed for the failure of Soviet agriculture since he sought to correct in a few years the neglect of a quarter of a century.

|

|