|

Nazi Rule in Germany, 1934 - 39 |

The Nazi System of Government and the concept of totalitarianism |

|

The thesis that Germany under the Nazis was a totalitarian regime was advanced in the 1950s by Carl Friedrich. Carl Friedrich maintained that a totalitarian state is one with the following six characteristics: (1) an official ideology; (2) a single mass party; (3) a state where the police use terror to control the people; (4) where the media is controlled by the state; (5) where the state has control over arms; (6) where the economy is centrally controlled by the state. This thesis has not been universally accepted in the case of Nazi Germany.

|

|

|

Germany became a one-party state in July 1933. However, the relationship between the Nazi party and the apparatus of the German state (civil service, judiciary and army) was not clarified at that moment. From 1933 there existence of the party and traditional state departments created confusion in government. Much of the German state machinery pre-dated the ascension to power of the Nazis. Thus, the laws initially enacted by the Nazi regime did not make extensive changes to the state apparatus. An example of this is the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service of April 1933, which made it impossible for Jews to be members of the civil service and likewise proscribed opponents of the regime from holding civil office, but otherwise made few changes. Although the Law to ensure the Unity of Party and State of December 1933 stated that the Party and the State were identical, the phrase in fact had little meaning. The Party was not in a position to take over government in 1933. It was an organisation that had been created to acquire power, not administer it once it had it; therefore, the Party had to rely on the pre-existing state organs. Additionally, the Party was not unified. In fact, during the course of 1933 there was a vast increase in Party membership and this diluted the influence of the older Nazis. The Party sought to reassert its authority after 1935 when Rudolf Hess, the Deputy Führer was given the power to vet all appointments and promotions within the civil service. In 1939 it was made compulsory for civil servants to be Party members.

|

|

|

The personal influence of Martin Borman also extended the control of the Nazi party over the people. Working with Hess, he created two new state departments: (1) The Department for Internal Party Affairs, which had responsibility for discipline within the Party; (2) the Department for Affairs of State, which sought to extend the control of the Party over the state. Borman become more personally influential after Hesse flew to England and was imprisoned there. It was Borman who turned the Party into an organisation capable of governing. However, the party always had to compete with the other state organisations for influence, and never wholly took them over, even if they were “emasculated”.

|

|

|

Theoretically, Hitler held unlimited power — he was both President and Chancellor, and also Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. He was extolled in documents and propaganda releases in terms that made him appear all-powerful within the state: “The position of Fürher combines in itself all sovereign power of the state,” as one contemporary constitutional document described it. However, in practice, no one man can control the whole state, and he requires subordinates that are willing to carry out his will. Additionally, Hitler lacked those personal qualities that make a leader practically effective. He did not like work, and did not like studying documents. He thought that things usually worked themselves out of their own accord, and he did not let people provide him with information. He thought that mere effort of the will was sufficient to accomplish something, and was not interested in coordinating government activities.

|

|

|

Some theorists, such as Hildebrand and Bracher, advance an 'intentionalist' thesis, in which they maintain that Hitler deliberately promoted chaos in order to divide one group from another and sustain his power by means of 'divide and rule'. Opposed to this is the 'structuralist' or 'functionalist' thesis advanced by Broszat and Mommsen that the chaos in government was a reflection of Hitler's limitations, and that the regime and policies of the Nazi party were concocted in response to circumstances and not through deliberate policy making.

|

|

Propaganda |

|

Goebbels became Minister of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda in 1933. He and Hitler recognised that the media had to be controlled by them. Goebbels instructed broadcasters in 1933 with the words, “And we will place the radio in the service of our ideology and no other ideology will find expression here..” At this time all radio stations were subsumed into one organisation, The Reich Radio Company. Jews and political opponents were dismissed. In order to increase the influence of the radio the government produced a cheap radio, the Volksempfänger (People's Receiver). Ownership of radios increased from 25% of German households in 1932 to 70% in 1939. Broadcasts were also made in public places, such as cafes, factories and offices.

|

|

|

There were a large number of daily newspapers in Germany — 4,700 in 1933. Most of these were privately owned, and made extending control over newspapers more difficult. The government formed a Nazi publishing house, the Eher Verlag, and this bought up newspapers so that by 1939 it controlled 2/3rds of the German press. A single news agency was created, the DNB, and Goebbels created a daily press conference. In the Editors Law of 1933 the content of a newspaper was made the sole responsibility of the editor, whose chief function was to act as a censor. However, the quality of the papers was poor, and readership declined by 10% between 1933 to 1939. The Reich Chamber of Culture controlled film, music, literature and art.

|

|

|

Goebbels introduced the Nazi salute, songs and militaristic uniforms to increase the influence of the regime over the individual.

|

|

The Apparatus of the Police State |

|

The SS developed into a separate organisation that was at one and the same time independent and linked to the State. The SS came to control the police. It was formed in 1925 as an elite body-guard for Hitler. It was not independent of the SA until Himmler was appointed its leader in 1929. By 1933 membership of the SS numbered 52,000, and the SS was dedicated to blind obedience to the Nazi cause. In 1931 Himmler created an internal police force, the SD (Sicherheitsdienst), which was responsible for policing the SS itself. Himmler also became chief of Germany's political police, the Länder, which included the Gestapo in Prussia. In 1933 Himmler was made Chief of the German Police. Himmler was subject only to Hitler, and the power of the SS grew enormously. The SS was responsible for all security concerns, and ran the concentration camps through its Death Head Units. The SS created its own military divisions which developed into elite fighting units in the Waffen SS.

|

|

|

The power of the SS was increased when Germany conquered large parts of Europe. Internal security also became a huge business — the Gestapo employed 40,000 alone. The size of the Waffen SS increased from 3 divisions in 1939 to 45 in 1945. The SS controlled the forcible movement and extermination of populations within Europe. It also created a commercial empire that controlled over 150 firms and used slave labour to produce anything from armaments to household goods. As time progressed the SS became the most influential body within the Third Reich.

|

|

The Army

|

|

Germany had a militaristic tradition, and leading generals were highly regarded. The Night of the Long Knifes strengthened the power of the army in the sort run. However, this increase of power was achieved by means of deal between the army and the Nazis that lead ultimately to the weakening of the power of the army. Symbolic of the transference of power from the army to Hitler personally is the oath of allegiance that all soldiers swore, from Field Marshal von Blomberg, the minister for War, and General von Fritsch, the Comander-in-Chief of the Army, down to all privates:

|

|

| I swear by God this sacred oath: that I will render unconditional obedience to the Fürher of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler, the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, and will be ready as a brave soldier to risk my life at any time for this oath. |

|

|

|

Initially, in the period 1934-37, there did not appear to be any significant diminution of the power of the army, and relations between the army and the party were friendly. The army's prestige was apparently strengthened by the programme of rearmament, and the introduction of conscription from March 1935, which increased the size of the army to 550,000 men. However, the strength of the SS was increasing, and Hitler did not regard himself as constrained by the army.

|

|

|

At a meeting at Hossbach in November 1937 Hitler announced a policy of war and conquest. Blomberg and Fritsch opposed this plan, but they were removed from office in February 1938 following slurs on their private lives. Blomberg's second wife was revealed to have had a criminal record for prostitution and theft, and Fritsch was accused untruthfully of homosexual offences. Following this, Hitler abolished the position of War Minister, and became Commander-in-Chief, establishing a new high command — the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) — answerable only to himself. Thus, the power of the army was diminished.

|

|

|

Officers in the army during the summer of 1938 plotted to arrest Hitler in the event of a European war at the time of the Sudenten crisis. But the plan was thwarted by the success of Hitler's foreign policy at this time.

|

|

|

Officers in the army plotted to assassinate Hitler during 1943 in the wake of the German reversals on the battlefield in North Africa and Stalingrad. Dissident generals, such as Beck and Rommel, were contacted by civilian resistance workers, and the plot eventually resulted in Colon von Stauffenberg planting a bomb in Hitler's briefing room in East Prussia on 20th July 1944. Although the bomb exploded Hitler received only minor wounds and the conspirators were arrested. A brutal enquiry was conducted by the Gestapo, and many leading officers were arrested or executed. The Nazi salute became compulsory within the army, political officers were appointed, Himmler was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Home Army, and the army was subordinated to the SS.

|

|

|

It is arguable that the army had aided and abetted Hitler in establishing a tyranny, and, whilst their plot to assassinate him was a brave gesture it came too late, and failed because of the compromised position in which army leaders had placed themselves.

|

|

The Jewish Persecution and Nazi Ideology |

|

Nazi ideology was inextricably interlinked with racism. Anti-semitism as been regarded as the “core” of Nazi thinking.

|

|

|

In place of the ideas of liberalism and individualism, Hitler upheld the idea of a communal interest — the Volksgemeinschaft or people's community. However, the idea was not clearly defined.

|

|

|

The Nazis did not invent anti-Semitism, nor was anti-Semitism a purely German attitude. However, in Germany anti-Semitism took a stronger hold during the late C19th. It was reinforced by racism and social resentment. Specifically anti-Semitic political parties were winning seats in the Reichstag prior to 1900. As industrialisation and urbanisation took root, the Jews were scapegoated and blamed for any social unease that arose.

|

|

|

|

|

|

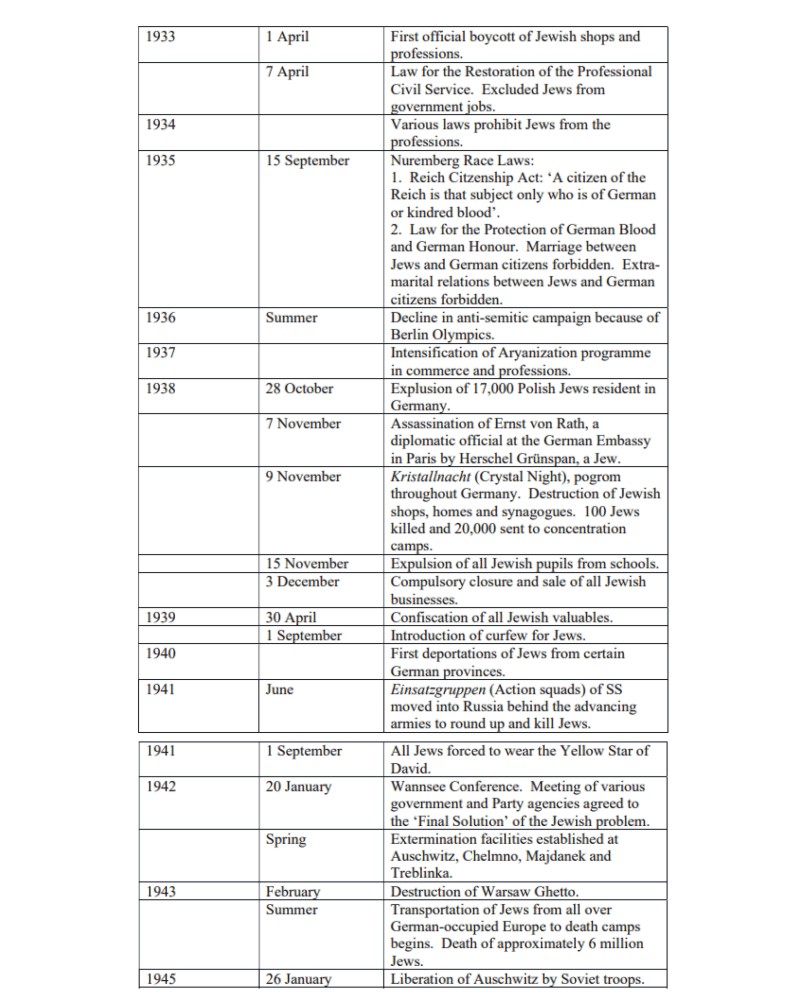

Chronology of Jewish Persecution, 1933-45

|

|

|

|

|

Hitler was himself a manifestation of the racial prejudice prevalent within German society towards the Jews. Hitler was able to manipulate for his own ends this inherent prejudice. However, it does not appear that the anti-Semitic element of the Nazi programme was what attracted average German support for it. In 1934 a survey asking why Nazis joined the party less than 40% mentioned anti-Semitism as a reason. This invites the question, if support for the anit-Semitic policies of Hitler was not so strong, why did so many Germans go along with it? Part of the answer is that the repressive measures against Jews were introduced gradually. Another part, is that after the establishment of the dictatorship from 1934 onwards, opposition to Hitler was futile, and the consequences of helping a Jewish person were dire. In response to the repression, between 1933 and 1938, 30% of the Jewish population emigrated; however, many opted to remain in Germany.

|

|

|

There is a debate over the exact role of Hitler in the extermination of the Jews. Intentionalists regard Hitler as the originator of the idea, but structuralists regard the 'Final Solution' as emerging from forces at work within Nazi society, and that Hitler was not solely responsible for what happened. Although there is no documentary evidence linking Hitler directly to the “Final Solution”, very few historians would doubt that he was fully aware of what happened.

|

|

Education and Youth |

|

The Nazis endeavoured to use education as a means of sustaining the dictatorship. They foresaw education as a means of indoctrination. In 1934 the Reich Ministry for Education and Science was given centralised control over education. Potential dissidents within the teaching profession were removed. Membership of the Nazi sponsored NSLB (Nationalsozialsitische Lehrerbund — National Socialist Teachers' League) rose to 97% of all teachers by 1937. Physical education was given prominence — 15% of school time. German, Biology and History were the most important academic subjects within the curriculum. German literature was taught so as to cultivate a militaristic mentality. Biology classes emphasised ideas of ethnic classification and racial genetics. Elite schools were created, including 21 Napolas (National Political Eudacational Institutions), and 10 Adolf Hitler Schools at secondary level; and at college level there were 3 Ordensburgen. Youth movements were sponsored: the DJ — Deutsche Jungvolk (German Young People) for boys from 10 to 14; the HJ — Htiler Jugend (Hitler Youth) for boys from 14 to 18; the JM — Jungmädelbund (League of Young Girls) for girls from 10 to 14; BDM - Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls) for girls from 14 to 18. For boys this entailed a large number of sporting and military activities, whilst girls were given domestic and maternal activities. Not surprisingly, it is estimated that academic standards declined during this period — especially at the elite schools. The Hitler Youth encountered particular difficulties. It expanded too rapidly and consequently was poorly led, and the diet of military drill was not appreciated by the boys. It is now believed that the youth movement induced alienation within young people towards the regime.

|

|

Religion |

|

Nazism was fundamentally opposed to Christianity, but initially Hitler did not directly attack any church organisations. Hitler regarded Christianity as originating from an inferior race, and he wanted to “stamp out” Christianity in Germany. However, at first Hitler sought to woo the Churches, and SA members were encouraged to attend Protestant churches. This aim was furthered by such events as the Day of Potsdam, when the Reichstag was opened at Potsdam following the March 1933 election during which the Berlin Reichstag building was burnt down. The ceremony involved many figures of national importance in a public display with Hitler, and it emphasised an apparent bond between the Nazis and the Protestant Church. The Catholics, too, sought a compromise with the Nazis, and in 1933 a Concordat was signed between the regime and the Papacy, in which the Catholic church promised not to intervene in State matters in return for a promise of freedom within its educational and pastoral domains. But the Nazis were insincere, and priests became victims of discrimination. The bulk of the Protestant Church broke away from that faction led by Ludwig Müller, the first Reich Bishop, and were led by paster Niemöller, who was later arrested and sent to a concentration camp. From 1935 onwards the Nazis became overtly hostile towards the Churches, and established a Ministry of Church Affairs to oversee the harassment of the Churches, with the abolition of denominational schools, attempts to vilify the clergy and further arrests of clergymen. The Papal encyclical of 1937 — With Burning Concern — attacked the Nazi regime. For a period of time, the persecution of the Churches abated, but following the Nazi victories against Poland and France, it intensified, and monasteries were dissolved and church property confiscated. However, only within the region of Warthegau in Poland were all clergymen executed and churches shut. The Nazis sought in place of Christianity to inspire a form of racial teutonic paganism, which was called the German Faith Movement. Church ceremonies of marriage and baptism were replaced by “pagan” equivalents.

|

|

|

There is some debate over the record of the Churches during the period. Some argue that the Churches failed to oppose an evil regime. However, it is an opinion that the Churches could do little, their emphasis on spiritual matters was understandable, and they were in fact only saved by the defeat of Germany.

|

|

Women and the Family |

|

Germany was following typical demographic trends for the period, and there was a decline in the birth rate from 2 million live births per annum in 1900 to below 1 million in 1933; hence, the rate of population increase was declining. Most German couples recognised that contraception and limitation of offspring would result in improved living standards. Additionally, the First World War had the effect of increasing the number of women in work. There was an excess of 1.8 million women of marriageable age, and many women had invalided husbands. There was also an increase in demand for manual labour, which increased demand for women in the workplace.

|

|

|

But the Nazi movement was ideologically opposed to the introduction of women into the workplace. They held a view that biological factors meant that a woman's place was in the home. They believed that an increasing population would be a sign of German vigour and would justify the acquisition of 'living space' within Eastern Europe. However, in these respects the Nazi ideology ran counter the development of the C20th of women's emancipation, and they were not able in practice to counter the prevalent trend. Between 1933 and 1936 it was made illegal for a woman to practice a profession, such as law or medicine. In June 1933 women were offered an interest free loan of 600RM if they were about to get married. But it was the Depression that caused the reduction of women workers, though not in absolute numbers: employment of women rose from 4.8 million in 1932 to 5.9 million in 1937, but this represented a decline in the percentage of the total workforce from 37% to 31%.

|

|

|

The Nazis introduced and enforced anti-abortion laws, and restricted the use of contraceptives. They created better maternity facilities and allowed one quarter of the marriage loan to become an outright gift. They extolled the virtues of large families and awarded decorations to mothers who had them. They enforced a eugenic policy that forcible sterilised people with hereditary diseases — 375,000 people in all. They introduced an institution that arranged for unmarried mothers to be 'impregnated' by members of the SS.

|

|

|

Nazi economic polices contradicted their ideological thrust against women's emancipation. Their rearmament programme led to a shortage of labour, and the proportion of women in the labour force began to increase again in response. By 1939 6.9 million women were employed, and the proportion had increased to 33%. In 1933 Speer recommended the conscription of women workers, but this was opposed by Bormann, Sauckel (Plenipotentiary for Labour), and Hitler.

|

|

|

In conclusion: Nazi policy towards women sought to reinforce a stereotyped image of a male dominated and lead society, but they were not able to affect the underlying trend for women to participate more and more in the labour market.

|

|

Cultural Life |

|

The Nazi attitude to culture is epitomised by the public burning of thousands of books on 10th May 1933 in a square in Berlin. In their view, culture should mould public opinion. A Reich Chamber of Culture was established in 1933, with seven departments — fine arts, music, theatre, press, radio, literature, film — and the aim was to propagandise the people and promulgate the cult of Hitler, anti-Semitism, militarism, and paganism, whilst rejecting cultural developments such as modernism, and repudiating Christianity. In music the Jewish composers Mahler and Mendelssohn were banned, and modernist composers such as Stravinsky, Schoenberg and Hindemith were disparaged. 2,500 German literary figures emigrated, including Thomas Mann and Bertold Brecht. No literature of any quality was produced in Germany during the Nazi period. The theatres played safe by mounting productions of German classics, and within the visual arts classical realism was promoted.

|

|

|

Only in the domain of film did Nazism produce any cultural flowering — the work of Leni Riefenstahl is still recognised by film critics as important for its use of novel film techniques and emotional appeal, despite the rottenness of the political message.

|

|

|

The Nazis stifled culture. However, they did not succeed in creating an alternative culture — and hence influencing the minds of the Volk (the people).

|

|

The impact on the Economy |

|

The revival of the economy made the German people more willing to accept or tolerate the regime. The working classes benefited from the stability in the economy: regular work and stable rents. Recreational activities were organised through the Nazi KDF movement (Kraft durch Freude — Strength through Joy.) However, with the end of the trades unions the working classes lost the power of free collective bargaining. Individual workers were forced from May 1933 to join the DAF (Deutsche Arbeitsfront — German Labour Front), which imposed employment conditions. During the period to 1938 real wages did not increase, whilst the average working week did — from 43 in 1933 to 47 in 1939. Workers in the rearmaments industries benefited most.

|

|

|

Farmers also benefited financially from National Socialism. Many farm debts were cancelled, and there was an increase in food prices between 1933 and 1936. Like the workers, however, farmers lost their independence. The Reich Food Estate was created in 1933, and had control over agricultural production and consumption. Its interference with the free market mechanism was much resented.

|

|

|

During the 1930s there continued to be a migration of workers from the land to the cities, where wages were higher. This created a labour shortage in the agricultural sector.

|

|

|

Whilst the Mittlestand — the German middle classes — expected to do well out of National Socialism, the Nazi economy simply sustained and even reinforced those forces that tended to squeeze this class out of existence.

|

|

|

Large businesses benefited most from the regime, and profits rose dramatically. For example, the share index was at 41 points in 1932 but rose to 106 points by 1940; dividends were 2.83% in 1932, but rose to 6.60% by 1940. Management salaries also increased, from an average of 3700RM in 1935 to 5420RM in 1938.

|

|

Explanations for the Emergence of the Nazi Regime |

|

Communists were initially at a loss to explain the emergence of fascism. The Seventh Congress of the Communist International in 1935 defined communism as, “the open terroristic dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinistic and most imperialist elements of finance capital”. The theory maintains that Nazism and capitalism are closely connected. Hence, this could be rendered consistent with Marxist thought — since Nazism could be interpreted as the last stage of capitalism, before it would collapse under its own weight. However, this view cannot be sustained in the view of the author. Whilst links between the Nazi party and industrial leaders did exist, Nazis were not merely the agents of these capitalists. Additionally, the Nazi party won a large proportion of the popular vote in democratic elections, and was therefore appealing to sections of the community other than the capitalists.

|

|

|

Another view of Hitler's Germany was put forward by the Chief Diplomatic Adviser to the British Government in 1941, Sir Robert Vansittart, who said in a series of radio broadcasts that 'Germany as a whole has always been hostile and unsuited to democracy”. A.J.P. Taylor supported this view, when he wrote in The Course of German History (1945):

|

|

|

“It [the Third Reich] was a system founded on terror, unworkable without the secret police and the concentration camp; but it was also a system which represented the deepest wishes of the German people. In fact it was the only system of government ever created by German initiative . . . it rested solely on German force and German impulse; it owed nothing to alien forces.”

|

|

|

In the post war period, historians from countries that were formerly at war with Germany tended to agree with the view expressed by Vansittart. For example, William Shrier, in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1959) wrote that Nazism was 'but a logical continuation of German history'.

|

|

|

German historians, particularly those that had opposed Hitler, were opposed to this thesis. Ritter, for example, emphasises the 'moral crisis of European society' as a whole. The cause of the disturbance is attributed to the shock to European society brought about by the end of the First World War, and other general trends, such as the decline of religion, the progress of materialism and the development of mass democracy, which demagogues such as Hitler could exploit.

|

|

|

However, it was Fritz Fischer's Germany's Aims in the First World War that brought the consensus among German historians to an end. In this work Fischer argued that Germany prior to 1914 had held aggressive plans of expansion, and that there was a uniformity of foreign policy between Imperial Germany and Germany under the Nazis. Fisher also approached German history in a novel way — and argued that there was a link between German domestic and German foreign policy during the Imperial period, with the elites defending their political power against social change. Thus, Fisher initiated a 'structuralist' approach to the interpretation of German history.

|

|

|

The structuralists argue that Nazism is not an accident in the development of German history, and focus on the continuing role of the social elites — particularly the armed forces and the civil service. They emphasise the common belief in Germany that Germany had a special position in history and a right to great power status. In their interpretation of Hitler's Germany they also draw attention to the limitations on Hitler's power — and the way in which it was, initially at least, built on a consensus of powerful interest groups.

|

|

|

Nonetheless, 'intentionalists' still argue that the responsibility for the rise of the Third Reich rests with Hitler principally. For example, the leading conservative historian of the 1960s, Karl Dietrich Bracher, argues that Hitler had a fundamental role in the state, and that Nazism can be equated with Hitlerism. His chief work, however, The German Dictatorship, does acknowledge that Hitlerism required a special climate in which to grow, and that was partly provided by the German/Austrian culture and partly by the circumstances of the conclusion of the First World War and the Depression. He continues to emphasise the charismatic power of Hitler.

|

|

|

He writes, “It was indeed Hitler's Weltanschauung and nothing else that mattered in the end, as is seen from the terrible consequences of his racist anti-semitism in the planned murder the Jews.”

|

|

|

In recent times there has been an increased interest in the history of everyday life during the period. This is an outgrowth of the structuralist approach, however, the social historians who have developed this approach have tended to distance themselves from the structuralist school.

|

|

Was the Nazi Regime a Totalitarian one? |

|

There were many totalitarian aspects to the Nazi regime; however, to describe Nazi Germany as 'totalitarian' would not be entirely accurate. It was a 'polycracy' instead — an alliance of different interest groups, the most important of which were: (1) The Nazi Party; (2) The SS-Police-SD system; (3) the army; (4) big business; (5) state bureaucracy. The Nazi party itself lacked the cohesion and unity of purpose that would be expected of a totalitarian regime. Private enterprise continued to exist — even if it was because industry sympathised with the Nazi regime.

|

|

|

However, the relative influence of the different power blocs underwent change as time progressed. The first significant point occurred in 1936 when Schacht was dismissed and the first Four Year Plan was introduced. This shifted power away from industry to the Nazi Party. In 1938 when Blomberg and Fritsch were dismissed, there was a shift of power away from the army to the Party. The war itself increased the power of the SS-Police-SD bloc, so that by the end of the war it was arguably the dominant power.

|

|

|

Within the Nazi regime itself there were many tensions and conflicts: Göring and Himmler were often rivals; Speer had many disputes with Sauckel (who was responsible for Labour). Borman and Goebbels were despised within the Party. However, the author does not accept that Hitler was a 'weak leader'. For the most part the regime was his creation, and no policy was adopted that was contrary to Hitler's wishes.

|

|

Did the Nazis Institute a Social Revolution? |

|

In David Schoenbaum's book, Hitler's Social Revolution, the thesis is advanced that Hitler was effectively a “powerful modernising force”. He draws a contrast between appearance and reality — or between 'objective' reality and 'interpreted' reality. Thus, Hitler's Germany appeared to be a regressive, repressive regime; but in reality it accelerated the modernising tendencies — for instance, for the introduction of women into the workplace.

|

|

|

However, other historians reject the idea that there was any social revolution under Hitler, arguing that the Nazi society was too transitory to leave any lasting mark on society. These historians argue that the real revolution was brought about by the destruction of Germany that was a consequence of the defeat of Nazism, which it is claimed resulted in the end to the social elites and interest groups that had formerly dominated German politics — particularly, the end of the influence of Prussian militarism and the Junker aristocracy.

|

|

|

Yet again, Marxists oppose both camps, arguing that Nazism reinforced traditional class distinctions, and strengthened the traditional elites — especially those of the military and capital.

|

|